Council of Europe needs encouragement from NGOs to launch online database on serious violations of media freedom

For many years the 47 member governments of the Council of Europe have had a blind spot about media freedom. They have been unwilling to give the go-ahead to any official mechanism that would monitor violations of media freedom in member states, as a first step towards a more proactive approach. Many media freedom NGOs have voiced their frustration at this block, regarding it as an affront to the urgent and important task of safeguarding the right (and the duty) of news media to act as a ‘public watchdog’ on the behaviour of over-mighty governments. That essential role of the media was established long ago and is frequently cited by no less an authority than the European Court of Human Rights.

A recent agreement in principle by the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers on this matter may open the way to a new and comprehensive online media platform dedicated to highlighting serious violations of media freedom as soon as they occur. But practical obstacles remain. It is not yet certain that such a website will actually materialise, because entrenched opposition still exists among some member states. Non-Governmental Organisations concerned with media freedom, including the Hungarian Europe Society and its affiliates, should be aware of this discussion and may wish to make their views known in order to help to bring the plan to fruition. The Committee of Ministers (CM) of the member states – meaning in reality the Ambassadors of all those countries at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg – meets regularly. Their role is to express the collective political view of the member States and to supervise the execution of judgements issued by the European Court of Human Rights. It is, as it were, the inter-governmental steering committee of the Council of Europe – the self-styled ‘conscience of Europe’. And down the years the Ministers’ Deputies (as they are called) have issued dozens of decisions, resolutions, recommendations and guidelines to the national governments on a wide range of media issues, from public service media governance to the promotion and protection of investigative journalism.

The CM often voices its concern, and suggests what priorities the Secretariat should follow, and endorses standards on various issues in line with the European Convention of Human Rights and the case law of the Strasbourg court. But the one thing the Committee of Ministers has not until now agreed to endorse is any ‘monitoring’ of media freedom violations in the Council of Europe area. Why? Essentially because the member States are ultra sensitive about any kind of outside scrutiny about the way in which their national authorities, law-enforcement agencies and courts deal with media affairs and journalists. Many of the most important and (for governments) difficult judgements of the court have been about violations by states of Article 10 rights – that is, the fundamental right to freedom of expression, including media freedom.

On 10 July the Committee of Ministers issued a Decision in which they agreed on the merits of ‘addressing an open invitation to interested media freedom organisations to report serious violations of media freedom’ to the Council of Europe. They also agreed, at France’s initiative, to consider ‘the modalities for the creation of an Internet based platform aimed at facilitating the compilation, processing and dissemination of the information’ so collected.

This wording may look clear-cut, but it is not yet a firm decision and the practical barriers are not small. So far no concrete plans have been drawn up on how to implement the proposal. The Media Division of the Secretariat of the Council of Europe has limited staffing and severely stretched financial resources, and it already has a substantial agenda of activities to take care of – including the organisation of a major Ministerial Conference of ministers responsible for media and information society issues in Belgrade on 7-8 November. To create and operate a real-time online portal of the kind proposed would be costly in terms of human skills and time. France has reportedly offered a sum amounting to a few thousand euros (not exceeding 5000 euros, according to the latest available information). Such a sum would easily cover the cost of creating a respectable-looking website, but would (one imagines) hardly fund the task of editing and supervising the posting of important material on it for more than a week or two.

In the view of this writer, this situation calls into question the strength of the real commitment of European governments to confronting the high and growing incidence of intimidation, threats, acts of violence and judicial and administrative interference with media freedom and the legitimate work of journalists that are evident and very well-documented in many parts of Europe. Indeed the Committee of Ministers itself drew attention to those negative and dangerous trends more than three years ago. Their Declaration of 13 January 2010 identified the task of strengthening effective protections for freedom of expression and media freedom as a priority area for Council of Europe action. They acknowledged that retrospective rulings by the Strasbourg Court – often five years or more after a violation has occurred – do not represent a sufficient safeguard. ‘Other means’, they stated, are essential to protect and promote freedom of expression and information and freedom of the media, and thereby to strengthen democracy.

One course of action which the Committee of Ministers approved in 2010 was to ask the Council of Europe’s Secretary General to make arrangements for ’improved collection and sharing of information’ in this field among the various parts of the Council of Europe itself – in other words a kind of ‘light touch monitoring’ system for serious media freedom violations. Yet insiders readily acknowledge that little or nothing has come of that as far as concrete actions to flag up and counter such abuses and violations are concerned.

Why does all this matter?

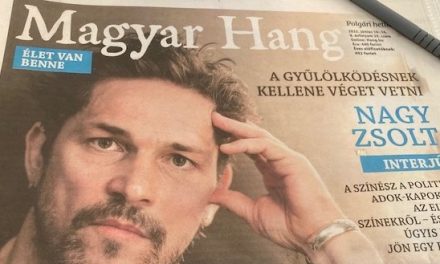

Increasingly in recent years governments’ attempts to control or stifle inquiring media have made big headlines. Violations of legitimate media freedom in many European countries have often provoked major political arguments within states, and they have severely embarrassed the European institutions which aspire to uphold press freedom as a cornerstone of open debate and democracy – namely, the Council of Europe, the OSCE and the European Union. Among the principal sources of concern are the numerous physical attacks on journalists in Russia; the jailing of scores of journalists in Turkey; the political interference in media affairs displayed by the Hungarian government through the current Media Laws; and the much-criticised concentration of media ownership in Italy over the past 20 years in the hands of former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and his allies. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, faces strong protests from other countries over the massive scale of surveillance of private communications carried out secretly by UK and US intelligence agencies (but now revealed by Edward Snowden to The Guardian); and the European Court of Human Rights is being asked to rule in a case concerning the use of terrorism laws to detain, search and seize materials in the possession of David Miranda, the boyfriend of Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald, in transit at Heathrow airport in August this year.

Even the Council of Europe, whose noble task is to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law, should be subject to fair scrutiny of its performance in delivering what it promises. Sadly, in the case of upholding media freedom, it has failed so far to deliver on its own pledges, especially those contained in the January 2010 Committee of Ministers Declaration on measures to promote respect for Article 10. The creation of a Council of Europe website devoted to flagging up issues of grave concern with regard to media freedom and the physical security of journalists would be a big step towards achieving the ‘visibility and impact’ for its activities in the field of media freedom, as the Ministers’ Deputies promised (again) in a Decision published on 18 January 2012.

It is not too late. The Ministerial Conference in Belgrade in November is expected to pass a Resolution on the Safety of Journalists, which is meant to lead on to new and practical measures to improve the safeguards for journalists and journalism in reality. But past experience shows that such promises are only likely to be fulfilled when the ‘stakeholders’ – meaning both expert civil society groups and concerned publics – speak up and demand that their elected representatives transform their vague pledges into actions with real ‘visibility and impact’. Media freedom is not the property of journalists or whistle-blowers alone. It is the mother of all freedoms – and too important to be left to politicians who naturally have their own interests to defend.

William Horsley has written three Background Reports since 2009 on the State of Media Freedom in Europe for the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), which are available on the AEJ website (www.aej-uk.org). Earlier this year he also wrote a Mapping Report on the Activities of Organisations in Europe working for the protection and safety of journalists and to combat impunity (http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/media/CDMSI/CDMSI(2013)Misc1_en.pdf) for the Council of Europe.. Details of the forthcoming Ministerial Conference of Council of Europe ministers responsible for media affairs http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/media/Belgrade2013/default_en.asp Recommended reading: Research Report by Prof Philip Leach (http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/media/cdmsi/CDMSI(2013)Misc3_en.pdf) on the principles which can be drawn from the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights relating to the protection and safety of journalists and journalism.