CFOM International Director William Horsley reports on a meeting to imagine routes to a safe environment for journalists.

The 2023 RSF Press Freedom Index highlights aggressive behaviour by governments towards journalists and the rapid growth of the “disinformation industry” as major factors in an increasingly bleak picture. What game-changing actions are really needed to reverse the trend, and even bring about a future in which State authorities willingly fulfil the legal obligations they have taken on through their UN membership, international treaties and other instruments? A meeting co-hosted by CFOM and the UN Association in London invited four speakers to put forward practical ideas to make that apparently fantastical idea a reality: a frontline journalist, a member of the High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom, the head of a UK-based NGO, and an authority on international justice and accountability.

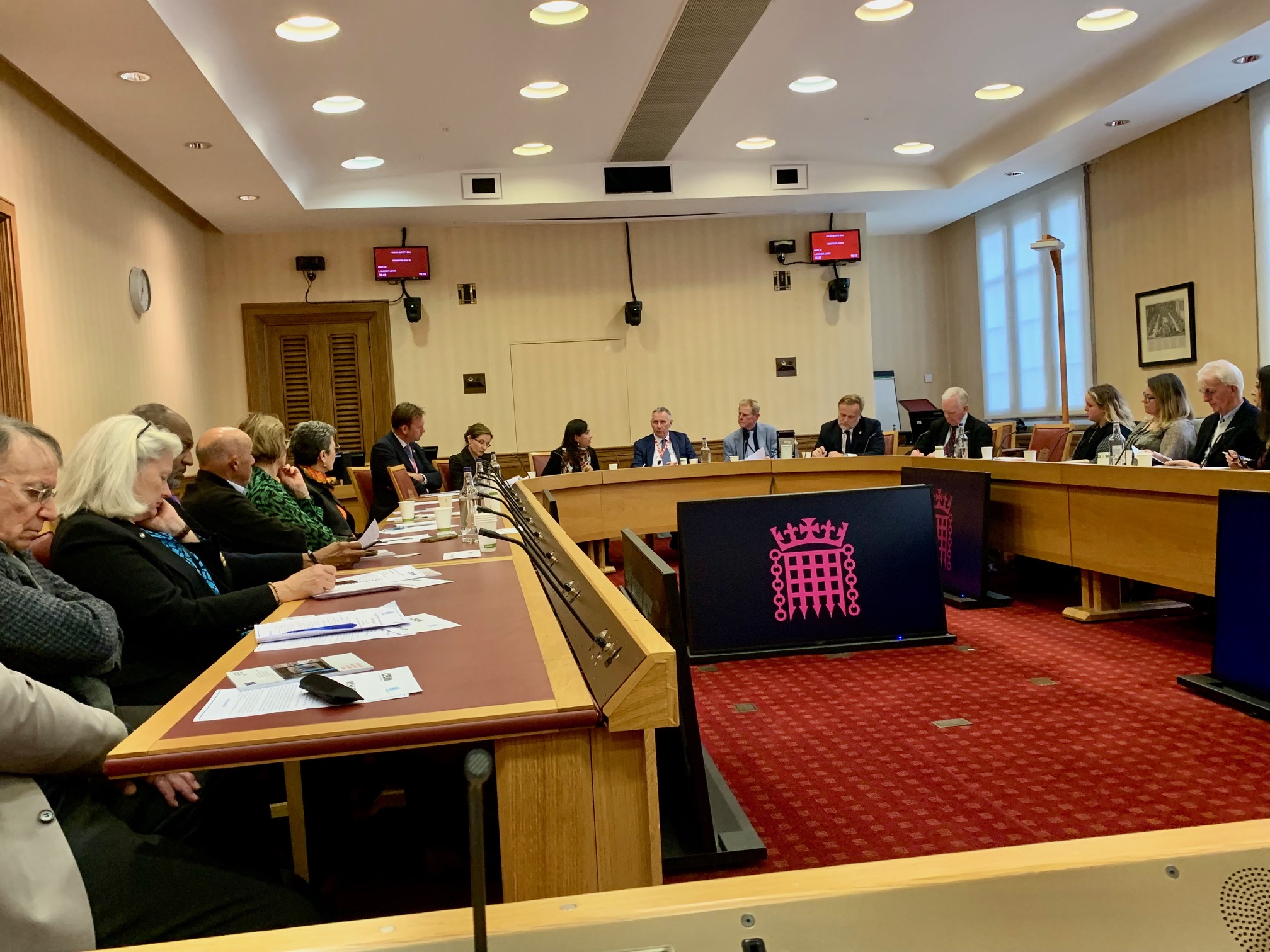

This thought experiment took place at a meeting held in the House of Lords (right) in the same week as the World Press Freedom Day gathering at the UN in New York, and it was underpinned by two developments. Firstly, the theme chosen by UNESCO for the 2023 World Press Freedom Day on 3 May is the special role of freedom of expression as a “driver” of all other fundamental rights. Secondly, representatives of the international academic community have resolved to coordinate policy-related research into seven fields, including the weaponisation of the law and the chilling impacts of impunity (the absence of accountability). Both are fields where state authorities have inalienable obligations

Image Credit: Doros Partasides

The long arm of hostile state powers

Amberin Zaman (right) is senior international correspondent for the independent online media Al-Monitor. She told the London meeting how her reporting on corruption and the Kurdish issue in her native Turkey brought her into direct confrontation with a state authority which has trampled on internationally agreed norms on protecting the public watchdog role of journalists. She faced politically motivated criminal investigations for “terrorism” and a warrant for her arrest. President Erdogan used speeches to large crowds – amplified by government-friendly media – to insult her as “scum” and brand her as “a militant disguised as a journalist”, while his bodyguards slandered her with impunity on social media as a “whore”.

Image credit: Al-Monitor

Amberin’s present home is London. In her words a “dystopian and violent climate” has enveloped not only her own country but many others too. While modern technology has enabled her to reach a wide audience through social media, the dangerous lack of controls or regulation against hate speech also makes her easy prey for intimidating “cyber-lynching” campaigns and vicious threats of sexual violence. As a result she suffered from being unable to attend her mother’s funeral in Turkey. Such unremitting threats and pressures take a heavy toll. And the physical dangers are growing: on a recent reporting trip to the Kurdish-controlled part of Syria Amberin was made aware of a potential risk to her life from a targeted drone attack. The over-mighty state today has a long arm regardless of borders.

Amberin Zaman called for a re-think of international priorities on the part of governments in the democratic world. Countries like the USA, Britain and France, she says, should be shamed as “hypocrites” when they fail to defend press freedom and journalists’ rights and instead choose to sell weapons and do business deals with foreign governments. National interest too often “trumps all other concerns!”. In 2018, the CIA investigated the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul and concluded he was killed on orders from the Saudi leader Mohammed Bin Salman himself. Yet President Joe Biden travelled to Saudi Arabia and shook the Crown Prince’s hand in an ultimately fruitless attempt to get him to raise the price of Saudi oil.

National governments’ attachment to arbitrary laws

Next the London meeting watched a video message from Karuna Nundy (right), a leading civil liberties lawyer and advocate at the Supreme Court of India. Nundy is one of 16 members of the independent High Level Legal Panel which since 2019 has advised the 50 member countries of the Media Freedom Coalition. The panel’s watchword is to “harness the authority of international law” to the effective protection of media freedom and the safety of journalists.

Nundy’s equally blunt message was that free speech has been brought to a “crisis” point by recent events, and concerted actions by the international community must ensure that fake news and manipulated information do not replace “edited facts” reported in good faith by independent journalists to inform the public. She pointed to the Indian government’s use of colonial-era sedition laws to silence critics, including, journalists, as an example of the contemporary misuse of arbitrary laws and untrammelled executive power by state authorities. Ironically, Mahatma Gandhi was prosecuted under those same laws, and he famously resisted them to advance the cause of India’s independence.

Nundy declared that the UK and other former colonial powers have a particular responsibility to ensure that “the remnants of colonialism” in such laws are removed or mitigated against. As part of the Panel’s ambitious mission to re-shape the global environment in favour of media freedom, its members issued a Research Report on 3 May advocating the reform of Blasphemy laws which are still in force in dozens of UN member states, and which breach agreed international standards of protection for speech. Nundy is the main author of that research report – the first of a series which will cover six key areas of legislation including national security, anti-terrorism, sedition and defamation.

The panel of legal experts has also published landmark Advisory Reports, recommending actions by willing states in four fields: 1) Targeted sanctions to protect journalists; 2) Safe refuge for journalists at risk in their own country; 3) Strengthening consular support for journalists working abroad; and 4) Effective investigations into the most serious attacks and abuses against journalists. Together, it is intended that the Advisory and Research Reports can serve as a practical guide to national governments, and help them to usher in a safer future for media freedom based on international norms.

Malicious actors and how to counter them

Journalists are under fierce attack from malicious actors, including totalitarian governments, dishonest politicians and unscrupulous corporate actors, said Maria Ordzhonikidze (right), the director of the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Her core demand is that faced with these malign forces, national governments which genuinely mean to defend press freedom should actively counter the “toolbox” of the enemies of press freedom, and also show good faith by establishing secure safeguards to protect the work and rights of journalists at home through legal and regulatory reforms.

JFJ was originally set up to facilitate journalistic investigations of crimes against media workers, following the brutal murder of three international journalists in the Central African Republic. Independent investigation linked this crime with the activities of Wagner mercenary group funded by Evgeny Prigozhin, a close associate of Russian President Putin.

Maria Ordzhonikidze highlighted the crucial and often violent part played by Russia’s doctrine of “information warfare” in political subversion and undeclared wars in many parts of Africa, the Middle East, and now in Ukraine. According to a senior official of Russia’s FSB (the security agency which replaced the KGB) this doctrine consists of “sabotaging the enemy’s infrastructure… hacking the enemy’s information resources, and winning over public opinion by spreading disinformation to influence public opinion and decision-makers.” Nowadays, hackers, troll factories, cyber-warriors and corrupt propagandists share the same aim of subverting democracy, while agents of influence and “useful idiots” are recruited abroad to advance that goal. Yet the UK has for many years failed to prevent the London courts from being misused by oligarchs and officials to bully into silence journalists, like Catherine Belton and Carole Cadwalladr, who exposed serious corruption and other crimes.

Maria’s practical proposals for a strengthening protections for press freedom include legislative reforms to introduce filtering and dismissal mechanisms enabling the courts to throw out clearly abusive cases before journalists are forced into long legal battles with crippling costs. She suggested that democratic states should treat propagandists the same way as war criminals, as well as prosecute trolls, doxxers and other malicious actors who assault the independent media. Maria also called for legal and visa assistance to help independent journalists exiled from authoritarian regimes with relocation and settlement abroad.

States which “weaponise” the law against their enemies

Finally Kingsley Abbott (right), who recently took over as Director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in London, focused on the misuse of law by states themselves. The key to achieving game-changing improvements in the safety and working environments for journalists was to hold them to the legally binding commitments which they had themselves voluntarily entered into.

Image Credit: University of London

By his count 173 of 193 UN member states were now signed up to the most important instrument which enshrines the universal right to free expression and the role of independent media in giving effect to democratic values – namely the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights (ICCPR). The core idea for this year’s World Press Freedom Day is the key role of free expression and media freedom in giving effect to a wide range of other civil rights, such as freedom of assembly, access to independent justice, and the right to vote.

Abbott identified two widely-peddled but false narratives or arguments used by states that are in clear breach of their international obligations. The first is the “special pleading” which says that for certain cultural, geographical or other reasons it is not possible for that particular state authority to fulfil its obligations under domestic or international law. A classic argument revolves around the alleged incompatibility of “Asian values” with universal ones. Kingsley recalled that in his former role as Director of Global Accountability and International Justice for the International Commission of Jurists, he frequently challenged those who advanced that excuse. His response to them was: “You chose to ratify the ICCPR, and your government is bound by Article 19 (the article that guarantees the fright to free expression) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); so what are you doing to comply?”

Next, he cried “foul” against the practice by certain governments – among them in his past experience Cambodia, for example – of “weaponising” bad laws adopted by that country’s legislature to silence critical voices, and then assert that the law must be respected because “we are merely applying the law” in our country. That argument is also false. Abbott insists it is a perversion of the law to prosecute or punish “offenders” under laws which themselves breach international legal human rights obligations.

Who will challenge the sovereign state?

The meaty and sometimes radical prescriptions proposed are all rooted in a commitment to established legal and democratic norms. But which authority can constrain the over-mighty state which chooses to break the rules?

Kingsley Abbott echoed the familiar call for a number of willing states to step forward as “champions” of media freedom. Maria Ordzhonikidze saw new hope in initiatives like the National Action Plans on journalists’ safety that have recently been set up in the UK and other places in response to a clamour of demands. Journalist Amberin Zaman praised the work of UN Rapporteurs and others who fulfil their mandates to monitor and sometimes challenge the actions of states, both large and small. “Reports about abuses that have taken place in a particular country are vital. When those things are put on the record by the UN, it gives a big boost to our reporting”, she said.

“Towards press freedom: new hope or false dawn?” was co-organised by the Centre for Freedom of the Media (CFOM), University of Sheffield, and the Westminster UN Association. The moderator was William Horsley, CFOM’s international director. The meeting was hosted by Lord Black of Brentwood.