Astrid Vandendaele, Assistant Professor of Journalism and New Media, discusses AI generated images and how journalists are adapting to using them in newsrooms

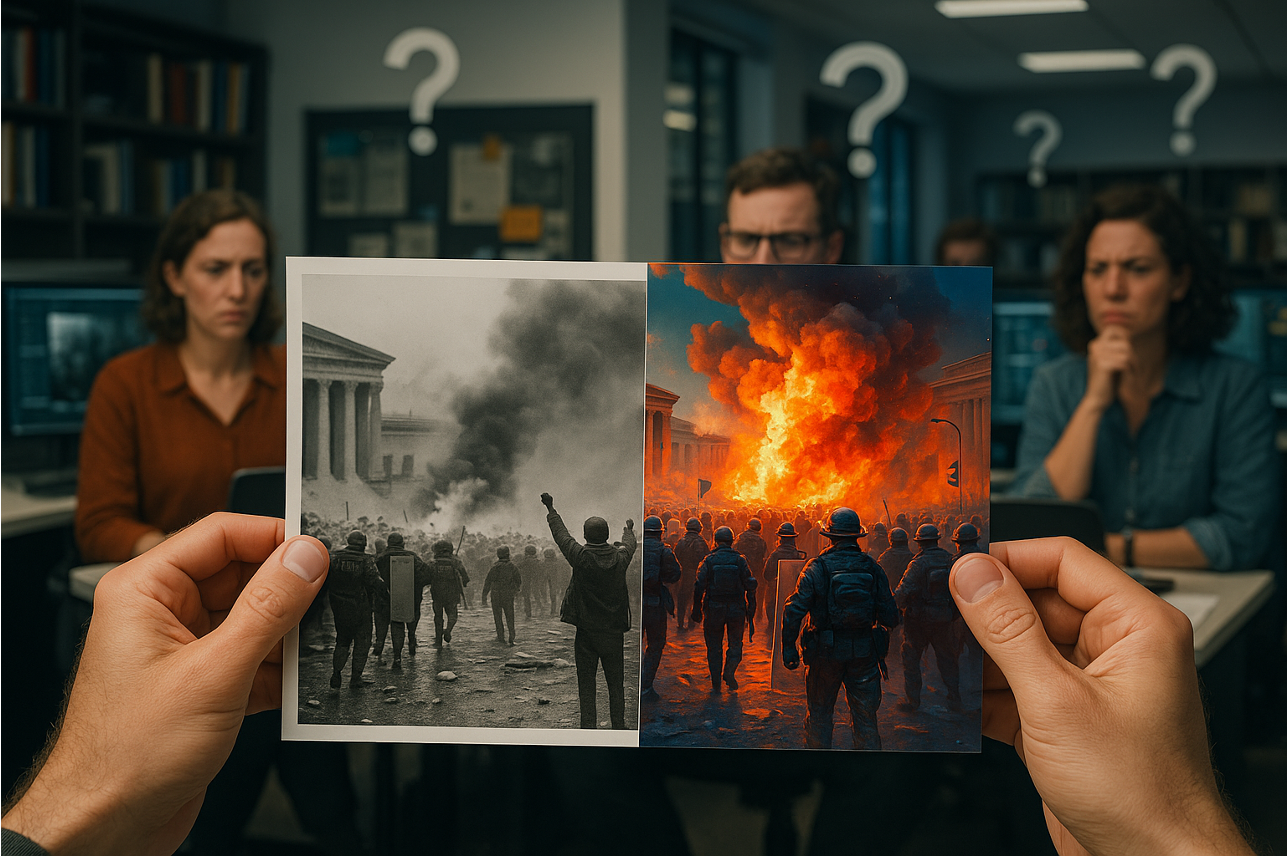

When an AI-generated image of an explosion near the Pentagon circulated online in 2023, the global media flinched. Financial markets trembled, social media erupted, and newsrooms scrambled to verify the source. It was not just another hoax—it was a warning flare for journalism. We have entered an era where the very fabric of visual evidence is unravelling.

As researchers and journalism scholars, we have spent the past year examining how generative AI (Gen-AI) reshapes visual journalism in the Netherlands. Alongside colleagues Jaap de Jong, Maartje van der Woude, and Stef Arends, I explored how Dutch newsrooms are navigating the promise and peril of synthetic imagery. We spoke to dozens of photo editors, visual journalists, ombudspersons and AI experts. What we found is sobering—and urgent.

Journalism’s Identity Crisis in Pixels

At its core, journalism is built on trust. We believe what we see. News photographs, more than text, carry an implicit claim to authenticity. But with generative AI, that assumption no longer holds. Tools like Midjourney and DALL·E 3 can now create photorealistic images in seconds, blending imagination with hyper-realistic detail.

While Gen-AI offers potential—cost savings, creative experimentation, and visuals for otherwise unfilmable events—it also destabilises journalism’s visual credibility. When every image could be fake, how can audiences distinguish true reporting from fabrication?

The paradox is acute: journalists must innovate, but without compromising the very standards that legitimise their work.

The Slow Uptake—and Why That’s Not Necessarily Good News

You might expect newsrooms to be rushing headfirst into AI experimentation. Instead, we found caution—even inertia. Many Dutch media outlets, especially national quality papers and broadcasters, use Gen-AI sparingly, if at all. Local and regional outlets (like Omroep Brabant), however, are somewhat more adventurous, experimenting with AI-generated newsreaders or explainer visuals.

But this caution is not necessarily a virtue. Often, it is the result of uncertainty, not principle. Newsrooms lack internal expertise. Visual professionals are wary of becoming obsolete. And perhaps most dangerously, there are few clear rules—no sector-wide guidelines, no legal clarity on copyright, no consensus on what constitutes “responsible use.”

In short: the train is leaving the station, but journalism is still staring at the timetable.

Guidelines or Gut Feeling?

One of our most striking findings was the absence of clear editorial policies, even though the need for them is real. As an image editor told us: “I think it’s very important that media outlets have a charter or at least a flow chart to decide in which cases automatically generated pictures are allowed. This is a discussion that each newsroom should have.” In many cases, decisions about whether and how to use Gen-AI visuals are made on a case-by-case basis, often guided by intuition rather than codified standards.

This ad-hoc approach is risky. Without shared norms, journalism becomes vulnerable, inconsistent, at risk of reputational damage, and manipulation. Some practitioners told us they worry that formal rules would stifle creativity or compromise press freedom. One of them warned: “What do you want to regulate? Are you going to tell the media what they must comply with? I believe the law should not interfere with what journalists do. Our task is to monitor the legislative power, not the other way around.”

But the greater danger lies in opacity. As AI advances, silence is complicity. In other words: by not acting, journalism may end up enabling the erosion of its own credibility.

We propose a middle ground: flexible, evolving guidelines co-created with newsroom staff, legal experts, and ethicists. These should cover sourcing, labelling, verification, and limits—especially for hard news. AI should assist journalism, not impersonate it.

Transparency: A Double-Edged Sword

The mantra “be transparent” is easy to chant. But how transparent is too transparent? Should every AI-generated image carry a watermark? A disclaimer? Metadata? We found divergence in both practice and opinion.

Some professionals worry that disclosing AI use might erode audience trust—even when the image is harmless or illustrative. Others argue the opposite: failing to disclose will backfire when audiences inevitably find out. One of the experts we spoke to explained: “You have to be transparent. Otherwise, it’s not journalism. But it’s not going to have any effect on trust.”

Our recommendation? Contextual transparency. Not every AI-assisted visual needs a screaming red label, but the public should never be misled. Think layered disclosure: labels for news images, footnotes for explainer graphics, and accessible explanations via ombuds blogs or reader forums. The key is to pre-empt misunderstanding, not fuel it.

The Skills Gap No One Talks About

Here’s a hidden danger: most visual professionals we interviewed feel under-equipped to deal with Gen-AI. They are experts in photography, graphics, design, or illustration—but not in prompt engineering or neural networks. Few have received training. Even fewer have access to internal expertise.

This “knowledge silo” problem creates asymmetries: between departments, between generations, and between editorial and tech staff. It also opens the door to accidental misuse. One interviewee noted: “There can be a kind of secrecy among journalists about it because there isn’t always an open conversation. I think creating space to experiment and openly communicate is very important.”

Case in point: the Dutch NOS aired an AI-generated penguin photo in a news item—without realising it was synthetic, which led the deputy editor-in-chief to write on the NOS website: “The simple explanation for this error is that we didn’t look carefully enough… Every image — even an illustrative background photo — in the NOS News broadcast must be real. Because you must be able to trust that NOS always shows the truth.”

To close this gap, we advocate newsroom-wide training—not just for tech staff but for (sub-)editors, producers, and reporters. AI literacy is not optional.

What’s Next?

Generative visual AI is not a passing trend. It is transforming how news is imagined, made, and perceived. The question is not whether journalism should use Gen-AI—but how.

Here are some recommendations for what we must do:

- Develop enforceable, newsroom-specific Gen-AI policies. Involve staff in the process. Make it a living document.

- Invest in AI education. Not just prompt skills, but legal literacy, bias awareness, and ethical reasoning.

- Design transparency practices fit for purpose. Think beyond “label or not” to how trust can be communicated across formats.

- Experiment (a lot)—safely. Innovation needs boundaries. Set them.

- Include the audience. If trust is the goal, don’t speak about users. Speak with them.

We also need regulators and journalism associations to step up. As one expert suggested: “Supportive peripheral organizations like unions, like journalistic bodies, professional associations can help in this space. They can develop some guidelines or help organizations develop their own.”

Self-regulation works best when it is guided by shared principles and societal oversight. Left to commercial platforms and tech giants, (Gen-)AI will evolve faster than any newsroom can react.

Final Image

One editor told us: “We used to fear Photoshop. Now we fear prompts.” It was partly a joke, partly a confession. The reality is more complex—and more urgent.

In the age of synthetic imagery, journalism faces an identity test. Will we retreat into nostalgia, fetishising the analogue? Will we rush into the AI arms race, hoping speed will save us? Or will we do the harder thing: reflect, regulate, and rebuild credibility—image by image?

Seeing is no longer believing. But believing in journalism? That is still worth fighting for.

Astrid Vandendaele, Assistant Professor of Journalism and New Media, Leiden University/Assistant Professor of Digital Journalism, Vrije Universiteit Brussel – June 2025