By Gemma Horton, Impact Fellow, Centre for Freedom of the Media

In recent years, the threats that journalists face have grown considerably. 2022 witnessed a rise in the number of journalists killed worldwide following a decrease over the past three years. 86 journalists lost their lives and the rate of impunity, according to UNESCO, is “shockingly high” at 86 per cent. The types of threats that journalists face have also diversified. The development of technology has meant that journalists are subject to online violence for the work that they conduct, particularly women who are being targeted and are vulnerable to such attacks as outlined in a recent International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and UNESCO report.

In recognition of the threats that journalists face, the United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity (UNPA) was launched in 2012 following endorsement from the UN Chief Executives Board. The UNPA was created with the aim to help create a free and safe environment for journalists to conduct their work. The UNPA encourages a multi-stakeholder approach between various actors, such as NGOs, media houses and governmental organisations, to campaign and raise awareness of the threats that journalists face. Academia has also been involved with studying the threats faced by journalists and understanding these threats.

The Role of Academia

Academia has played a large part in implementing the UNPA and also being involved in World Press Freedom Day. For example, in 2016, the Journalism Safety Research Network (JSRN) was launched at UNESCO’s research conference on the safety of journalists. The JSRN has continued to grow since its inception, now hosting over 250 researchers who work at universities, research centres and civil society organisations in over 50 countries. It regularly hosts events surrounding thematic and regional journalism safety issues and has just launched its Regional Working Groups in order to further facilitate the exchange of knowledge in relation to journalism safety issues.

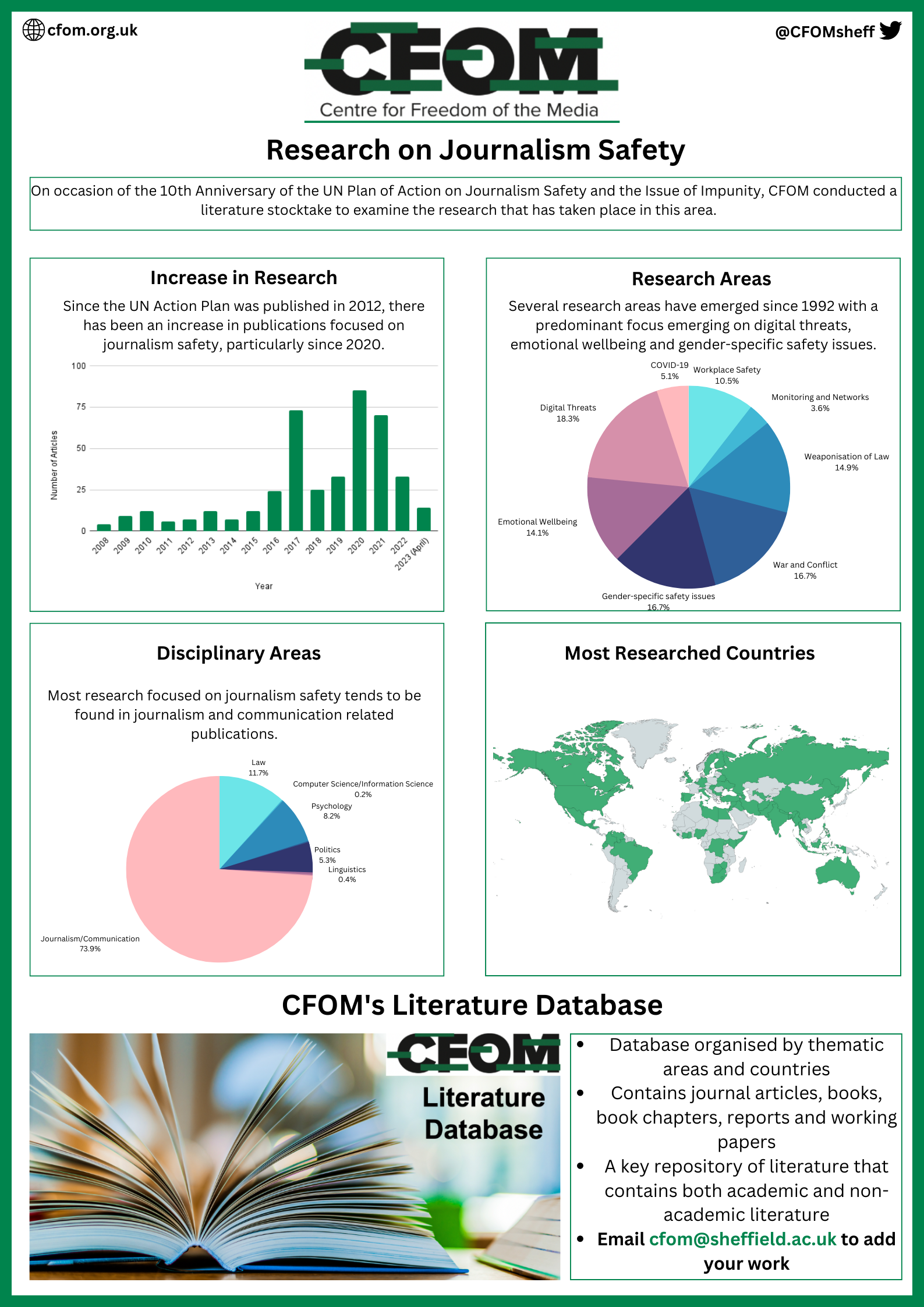

Alongside a growing and vibrant network, academic research has concerned itself with asking questions about current issues concerning journalism safety in order to understand these in greater detail. Academic research in recent years has focused on current phenomena and this was evidenced by CFOM’s academic stocktake that took place on occasion of the 10th anniversary of the UNPA. The academic stocktake revealed particular trends and these shall be summarised below.

Growth in research and topics

Research on journalism safety pre-2012 tended to have a focus on specific events that were taking place. For example, the early 2000s witnessed the publication of literature focused on the role of international humanitarian law to protect journalists during war and conflict occasioned by both the Afghanistan and the Iraq wars. There was also an emerging literature dataset on the psychological well-being and issues of PTSD that manifest in war correspondents. However, since the implementation of the UNPA in 2012, research surrounding journalism safety has grown. For example, from 2012-2015 there were around 5-10 publications published annually. Since 2016, the number of publications has been consistently around 25-30, with notable exceptions in particular years. For example, in 2017 there were 73 publications, in 2020 there were 85 and in 2021 there were 70. The range of topics has also grown since the implementation of the UNPA and there is also an emphasis on focusing on specific countries in research, with Mexico being the most researched country in academic literature with 29 pieces centred on it and Pakistan coming a close second with 26 pieces. Academic research has also focused predominantly on seven main research areas which will be discussed in further detail:

- Digital safety

- Gender-specific safety issues

- Trauma, resilience and mental health

- Workplace safety

- Monitoring and networks

- Impunity and its impact

- The weaponization of the law

Diversification of Research Topics

Digital Threats

The online harassment of journalists has been documented as a growing concern by the UN with UN Resolutions calling on States to address digital security threats and journalists being victims of online trolling. The recent JSRN symposium focusing on digital threats highlights the work that academia is conducting in this area. One area of focus is online harassment with it being noted that women are more likely to be subject to online harassment than their male counterparts. Research has also started to consider the concept of the perpetrator more closely, such as by identifying politicians who incite verbal violence and how this can lead to self-censorship. Along with online harassment, academia has also focused on digital threats, such as online surveillance and digital shutdowns and how a lack of training places journalists at risk.

Gender-specific safety issues

Alongside being subject to online harassment, women journalists are also more likely to suffer from harassment in the workplace. Research has evidenced that they suffer from sexual harassment, sexist comments and are subject to gender inequality. A culture of silence surrounding (sexual) harassment is also found to exist in many places, with research showing that women journalists do not complain about such harassment out of concerns about how their bosses would handle their complaints. As a result of this, they have developed coping mechanisms, avoidance strategies and also self-censor themselves.

Emotional and psychological wellbeing of journalists

Increasingly, academic research has examined how journalists can suffer from ‘every day’ trauma. While research has examined how journalists suffer from trauma as a consequence of being present at traumatic events, such as terror attacks, there has been a shift to recognise that journalists can suffer from trauma while in the newsroom. For example, news-gathering processes in newsrooms involves looking at user-generated content and visual images that can lead to what has recently been referred to as ‘everyday trauma’ (Kim and Shin, 2022). Academic research has also revealed that, in general, there tends to be a reluctance by media houses’ to engage with journalists’ emotional wellbeing. Encouragement has been made by the academic community for more to be done with regards to training journalists and also providing them with a space to be able to talk to their employers about their mental health too.

Workplace Safety

Alongside acknowledging the need to protect journalists’ psychological wellbeing, it has also been noted how, in other instances, newsrooms do not offer adequate safety training. For example, in countries considered hostile environments, it has been stated that journalists should be given culture and language seminars and, in some instances, be trained in international humanitarian law so that they know their rights. They should also be given safety kits to protect them and this was noted as being of the utmost importance during the COVID-19 pandemic with masks and hand sanitizers being of particular importance for journalists who were still working in the field.

Monitoring and Data Collection

Research has also highlighted how important monitoring is in collecting data on journalism safety and how there needs to be extensive collection of data on violations against journalists. Big data case studies produced by the ICFJ emphasise this to be the case as, in the past, academic literature highlighted how there was a lack of methodological transparency in data collection. In order to improve monitoring, there is also a need to widen definitions on who is considered a journalist in order to gain the fuller picture of the types of violations taking place. For example, citizen journalists, social media actors and indigenous journalists are not included in data collections and should be.

Impunity

Issues concerning impunity have also been researched in academic research, namely by focusing on who the perpetrators of impunity are. In some instances, these have been documented to be states through state-sponsored actors, including drug cartels, Organised Crime Groups and terrorist groups. In addition, the state and statesmen themselves have recently become more involved in harassing journalists online. For example, Donald Trump’s attacks on the media have had a long-lasting impact in the United States and President Modi in India has been critical of journalists, with his supporters involved in conducting online attacks against them.

The weaponisation of the law

Freedom of expression is seen as a fundamental right that is necessary in order for journalists to be able to go about their work freely. However, academia has noted that in certain countries this is not the case and freedom of expression is not protected through legislation. Even in countries where legislation might exist, the fact remains that it needs to be enforced by governments. This can be through criminalising attacks against journalists and ensuring that perpetrators are held accountable for their action. In other instances, the law is used by governments to silence journalists through the enactment of certain pieces of legislation and also the increase of the use of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs).

Moving forward: a pressing need for academic research

The volume of academic research and the breadth of topics covered continues to grow. As threats to journalists diversify in this digital age, it is imperative that academic research continues to explore these numerous issues in order to understand their origin and engage with stakeholders in both the academic and non-academic sectors to work together to find the best ways to tackle these issues.